CAM Investment Grade Weekly Insights

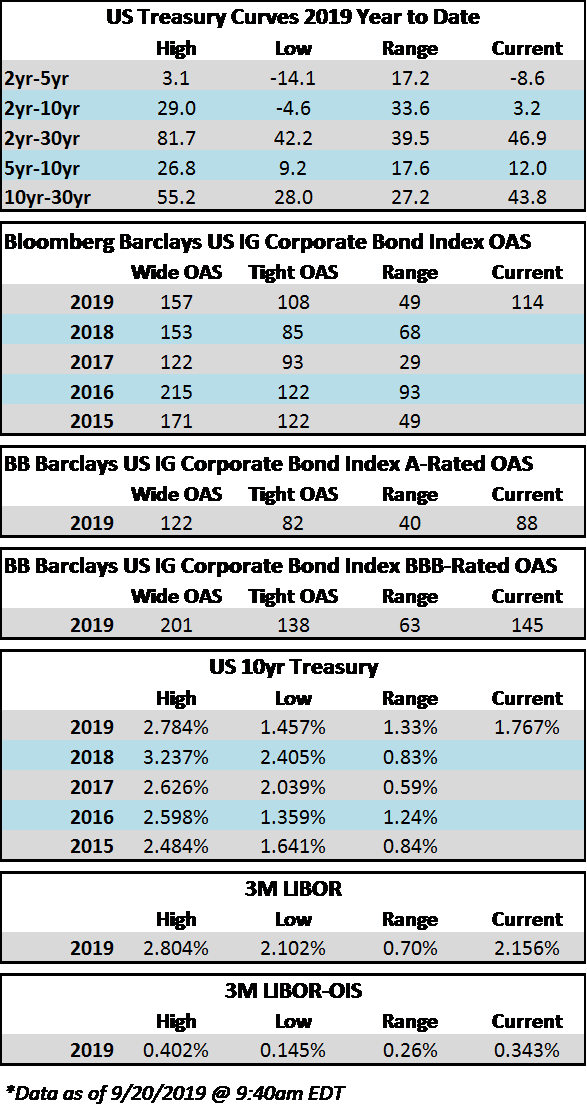

Spreads are tighter on the week and Treasuries are lower. The OAS on the corporate index opened the week at 116 and is 114 as we go to print on Friday morning while the 10yr Treasury is at 1.767%, 12 basis lower from the previous Friday close. In other news, as expected, the Fed cut the target rate on Wednesday by a quarter-point to 2%. The direction of future cuts is much less clear with plenty of debate as to whether or not the Fed will cut again this year. We tend to think it comes down to economic data and the Fed has been quite clear about this in our view. The Repo market made headlines throughout the week due to a spike in repo-rates amid a supply-demand mismatch. The Fed has since intervened and gotten the rates under control. It remains to be seen as to whether this is much ado about nothing but so long as the Fed liquidity injections can manage to keep rates within the targeted range then we believe that this topic will go by the wayside.

In what seems to be a recurring theme, the primary market had yet another strong week. Monthly volume has topped $140bln for September making it the 8th busiest month in history with more than a full week to go. Year-to-date supply is now $905bln which is down a smidge less than 4% relative to 2018 supply at this juncture. While it was a busy week in the primary market it was not quite as robust as the previous two –if $37bln manages to price by the end of the month then September 2019 would become the busiest month on record but with just 6 trading days left and quarter end looming we are probably not likely to see enough supply to topple the all-time high.

According to Wells Fargo, IG fund flows during the week of September 12-18 were +$2.5bln. This brings YTD IG fund flows to +$213bln. 2019 flows are up 8 % relative to 2018.

(Bloomberg) The Repo Market’s a Mess. (What’s the Repo Market?): QuickTake

(Bloomberg) The Repo Market’s a Mess. (What’s the Repo Market?): QuickTake

- When plumbing works well, you don’t need to think about it. That’s usually the case with a vital but obscure part of the financial system known as the repo market, where vast amounts of cash and collateral are swapped every day. But when it springs a leak, as it did this week, it rivets the attention of the U.S. Federal Reserve, the nation’s largest banks, money-market funds, corporations and other big investors. The Fed calmed things down by pumping in billions of dollars, but it may have a lot more work to do on the pipes.

- What’s the repo market?

- It’s where piles of cash and pools of securities meet. Repo is short for repurchase agreements, transactions that amount to collateralized short-term loans, often made overnight. Repo deals let big investors — such as mutual funds — make money by briefly lending cash that might otherwise sit idle, and enable banks and broker dealers to get needed financing by loaning out securities they hold in return. A healthy repo market is more than the world’s biggest pawn shop: It helps a wide range of other transactions go more smoothly — including trading in the over $16 trillion U.S. Treasury market.

- How is the Fed involved in it?

- In a number of ways. For years, central banks around the globe have used their own repo markets to extend credit in tight markets, stabilize financing costs and guide interest rates. But the relationship changed when the U.S. repo market melted down in September 2008, a crucial part of that year’s financial panic. Since then, the Fed has worked with other regulators to put in new rules to prevent a recurrence. And since 2013, the Fed has entered the repo market on a large scale, using transactions there to put a floor under rates.

- What happened this week?

- A lot of cash flowed out of the repo pipes just as more securities were flowing in — meaning that suddenly there wasn’t enough cash for those who needed it. That mismatch drove overnight repo rates from about 2% last week to over 10% on Tuesday. Perhaps more alarming for the Fed was the way volatility in the repo market pushed the effective federal funds rate to 2.30%, above the 2.25% upper limit of the Fed’s target range — just as the Fed was preparing to drop that ceiling to 2%.

- Why did that all happen?

- In one view, different events that acted as catalysts just happened to land at the same time and push in the same direction. A big swath of new Treasury debt settled into the marketplace, landing on dealers’ balance sheets just as cash was being sucked out by quarterly tax payments companies needed to send to the government.

- What did the Fed do?

- In its first direct injection of cash to the banking sector since the financial crisis, it laid out about $200 billion in temporary cash over several days to quell the funding crunch and push the effective fed funds rate down. In what are known as overnight system repos, the Fed lent cash to primary dealers against Treasury securities or other collateral.

- Was that enough?

- It did calm the markets, eventually bringing the rates down around 2% on Thursday. And the action may be sufficient for a temporary patch, if the liquidity squeeze really just reflected the corporate tax payments and Treasury settlements falling on the same date. But most strategists and economists believe the turmoil is a sign of a longer-term problem. To some, one factor is that the rules regulators imposed to make the market safer led dealers to pull back on their involvement, reducing overall liquidity. And many think these distortions will continue as long as government spending and Treasury’s debt issuance continues to rise. More broadly, some observers say that the repo troubles show that there aren’t enough reserves — excess money that banks park at the Fed — in the banking system to give markets the buffers they need at times of stress.

- What does that mean?

- To some market observers, it might mean that bank reserves, which currently top $1 trillion, still don’t amount to having enough money in the system. They think the Fed may have to start buying bonds again as a way of boosting reserves. This time the purchases would not be like the quantitative easing of the past, meant to support the broader economy, but just to clear up the mechanics of its balance sheet. As with any corporation, the Fed’s assets and liabilities must balance. The Fed’s liabilities mainly come in the form of currency in circulation and bank reserves. As the nation’s economy expands, as it has since 2009, the amount of currency in use has been growing, too. Without action by the Fed to add to its assets, the growth of currency would reduce the liability represented by reserves.

- What can the Fed do about the repo squeeze?

- It did one thing at its September meeting, and two other steps are being discussed. It lowered the interest rate it pays on so-called excess reserves — the cash banks park at the Fed beyond what’s needed to meet regulatory requirements — to 1.8% from 2.1%. Lowering the IOER rate — interest on excess reserves — gives banks an incentive to lend out more of their money, which would keep repo and the effective federal funds rate more within the Fed’s target range. The Fed has also considered introducing a new tool, called a standing overnight repo facility, which would amount to a standing offer to lend a certain amount of cash to repo borrowers every day. The most drastic step would be for the Fed to create more bank reserves by expanding its balance sheet and thereby buoying bank reserves. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said Wednesday that the central bank is monitoring when it’s appropriate to start expanding the balance sheet.

- What’s the repo market?