CAM Investment Grade Weekly Insights

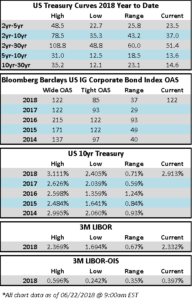

Trade concerns continued to weigh on debt and equity markets throughout the week. Spreads on the Bloomberg Barclays Corporate Index are 7 wider on the week as we go to print on Monday. A deluge of corporate bond supply in the primary market has certainly helped to push spreads wider. On Monday, Bayer printed a $15bln deal to fund its acquisition of Monsanto. At the time, this was the second largest deal of the year, after the jumbo $40bln deal that CVS brought to market in early March. Walmart would soon take the mantle of the second largest deal from Bayer as the retailer brought a $16bn deal on Wednesday to fund its acquisition of Indian-based ecommerce retailer Flipkart.

According to Wells Fargo, IG fund flows for the week of June 14-June 20 were -$1.4 billion. Even with the reversal in flows, IG flows are still positive at +$68.107 billion YTD.

Jumbo M&A led to one of the busiest new issue calendars that we have seen thus far in 2018. Per Bloomberg, over $43 billion in new corporate debt priced through Thursday. This brings the YTD total to $636 billion.

(Bloomberg) Why Corporate Bond Liquidity Might Not Be as Bad as You Fear

- Banks’ shrinking corporate-bond holdings are partly a statistical mirage, according to a consulting firm. Some money managers and analysts believe it may be time to stop worrying about it.

- One measure of total dealer holdings of corporate bonds has dropped by around 90 percent since the crisis, a fact that has instilled fear in money managers for years. Dealers’ inventories of corporate bonds can be a shock absorber for the market: in times of trouble, banks can buy the securities from panicked sellers, hang onto them, and then offload them slowly, potentially preventing prices from plunging.

- But the decline in inventories is less dramatic than it seems because of a quirk in the data, consulting firm Tabb Group wrote in a recent report. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York statistic in question, primary dealer positions in corporate securities, fell to around $23 billion as of June 6 from around $265 billion in 2007. Much of that decline stemmed from the New York Fed narrowing the way it defined corporate bonds in 2013, when it appeared to have removed mortgage-backed securities without government backing from the mix, according to Tabb. On an apples-to-apples basis, inventories declined more like 35 percent to 50 percent for banks between 2007 and 2014, the consulting firm estimated.

- Inventories aren’t even the best measure to look at for assessing liquidity, Tabb Group said. What money managers care about is a bank’s capacity to buy securities, and the bigger a dealer’s inventory, the less ability it has to buy more. The average capacity at the six biggest U.S. banks for corporate bond underwriting fell just 16 percent between 2006 and 2017, according to Tabb, and most of the banks can take on even more risk if there’s a valid business reason to do so.

- Looking at the top 20 dealers, the decline in banks’ capacity from the pre-crisis era is closer to around 35 percent, Tabb estimates. But it’s not fair to completely blame rulemakers for these declines. There are good business reasons for banks to be less willing to hold the debt because interest rates are broadly rising, said Timothy Doubek, senior portfolio manager at Columbia Threadneedle Investments, which manages about $172 billion of fixed income assets.

- There are still reasons to be worried about how corporate bonds may perform in a downturn. The declines in inventories and capacity have come at a time when the amount of debt outstanding has surged: there were about $9 trillion of U.S. corporate bonds outstanding as of the end of March, according to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, a trade group. That’s an increase of around 85 percent from the end of 2006.

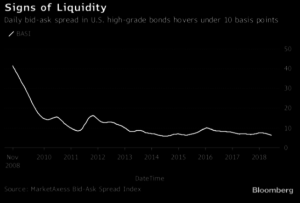

- There’s no single way to define liquidity and it can vanish during times of stress. One measure known as the “bid-ask spread,” which looks at differences between the prices at which dealers will buy and sell a security, tends to grow wider when liquidity is low, and shrink when it’s strong. That spread is about as tight as it’s ever been.